You asked: How much would a national nuclear bailout cost taxpayers?

So, we did the math.

There are two answers to this question, based on two different pieces of proposed legislation: the Senate bipartisan infrastructure deal and a bill jointly introduced in the House and Senate (H.R.4024/S.2291), which the sponsors want included in the Democrats’ infrastructure bill: the American Jobs and Families Plan.

The bipartisan bill includes a total of $6 billion over five years (2022-2026) for a Civil Nuclear Credit program. Unprofitable reactors can apply for the credits, which the Department of Energy (DOE) would award to all which qualify. The cost for the five years is capped, but the bill includes the possibility of extending the program an additional five years, through 2031. In that case, the total cost would be $12 billion over 10 years (2022-2031).

The other bill, titled “The Zero-Emission Nuclear Power Production Credit Act of 2021,” does not contain a firm cost cap, but we can estimate the total cost. The bill would provide a tax credit to eligible nuclear power plants for 10 years (2022-2031), reducing the taxes they owe based on how much electricity they generate. All “merchant” nuclear power plants could qualify for the tax credits: merchant power plants are owned by companies that sell their electricity through competitive markets or directly to customers through contracts; as opposed to utility-owned reactors, which recover their costs through electricity rates approved by the state government.

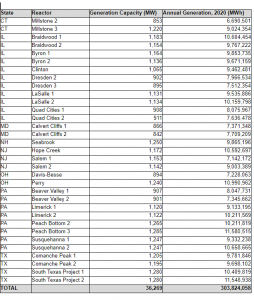

There are currently 40 merchant reactors operating in the U.S.—about half of the total in the U.S. For various reasons, seven of those reactors likely would not qualify for the credits, despite their merchant status:

- One reactor in Michigan is slated to close in 2022 (Palisades).

- Two reactors in Wisconsin have a contract through which to sell their electricity at very high prices until 2032 (Point Beach 1&2).

- Four reactors in New York are receiving much more lucrative subsidies through a state program until 2029 (FitzPatrick, Ginna, and Nine Mile Point 1&2).

Of the other 33 merchant reactors, all would likely qualify for the H.R.4024/S.2291 tax credit and most may qualify for the Civil Nuclear Credit in the bipartisan bill.

bill.

That includes eight reactors in three states (CT, IL, and NJ) which are already receiving subsidies that are charged to consumers. Those states might cancel those subsidies if the federal bill is enacted. The nuclear production tax credit would be even greater than what the states are providing to those plants, so it would be in the interests of both the nuclear corporations and consumers to take the federal tax credit and end the state subsidies in CT, IL, and NJ.

So, in total, up to 33 reactors could receive the production tax credit. Let’s crunch the numbers. In 2020, those reactors generated 303,824,058 megawatt-hours of electricity.

The tax credits would provide $15 per megawatt-hour (MWh). At that rate, the total cost of the bailout would be $4.6 billion/year or $45.6 billion over the 10-year period.

The Adjustment Provision

The bill does include an adjustment to the tax credit based on market prices for electricity. For nuclear power plants that earn market revenues in excess of $25/MWh, the amount they receive in the production tax credit is reduced by 80% of the difference. That means, if a reactor earned $28/MWh on the competitive market in a given year, the difference would be $3/MWh. The production tax credit it receives would be reduced by 80% of $3, or $2.40/MWh. The company would receive a production tax credit of $12.60/MWh. Similarly, if the company earned $40/MWh on the market, the tax credit would be reduced accordingly:

- $40/MWh (market revenue) minus $25/MWh = $15/MWh (difference)

- $15/MWh times 80% = $12/MWh (tax credit adjustment)

- $15 MWh (base tax credit) minus $12 MWh = $3 MWh (adjusted tax credit)

That nuclear power plant would still receive a subsidy of $3/MWh—for total earnings of $43/MWh. Inexplicably, the subsidy would be set up to ensure that reactors that might be profitable on their own still get a taxpayer subsidy that would make them even more profitable to operate.

The nuclear industry might claim that this adjustment provision would greatly reduce the actual cost of the subsidy to far less than $46 billion. In principle, if electricity prices broadly trend upward in the next decade, it is possible that could happen. However, there is no guarantee of it, and there is good reason to assume the opposite, especially for budgeting purposes. Market electricity prices have been decreasing for over a decade, and that could well continue as renewable energy grows and natural gas generation declines.

Electricity sources are typically required to bid their power into the market at their “marginal cost of generation”—that is, the amount it costs them to generate the next MWh of electricity versus what their costs would be if they did not generate electricity. The main driver of marginal prices today is the cost of fuel to run power plants: primarily coal, gas, diesel fuel, and biomass. For wind, solar, and hydro, which have no fuel costs and minimal to zero staffing costs, they bid $0, reducing the overall price of power in the markets. In contrast, nuclear power plants buy all of their fuel at once, every 18-24 months. The cost of nuclear fuel is treated more like a capital cost the company will pay off over time, but with $0 marginal cost.

Fracked gas prices can be quite volatile, depending on weather conditions and peak electricity demand. When demand for gas or electricity is high, the price increases; and when supply is short while demand is high, the prices can get very high. But the costs of fracked gas have remained quite low for years, even with infrequent, localized spikes. As renewables, storage, efficiency, and demand response expand over the next decade, demand for gas will decrease and the patterns of peak pricing will change as well. It is quite possible that gas prices and average market prices for electricity will trend lower, rather than increase.

There is real-world experience to justify this caution. The current state nuclear subsidy program in New York includes a market price adjustment like the one proposed in the nuclear production tax credit bill. But market prices have remained low in NY, and the state subsidies have maxed out with no price adjustment. By contrast, Illinois’s current nuclear subsidy includes a total cost cap, which has reduced the amount ratepayers have been charged for nuclear subsidies. Based on these trends and the experience with the state programs, the cost of the proposed federal nuclear production tax credit should be estimated at the maximum level. Based on the number of reactors that could be eligible, that would be $46 billion over 10 years. If both of the nuclear subsidy proposals are enacted, the total cost could top $50 billion.

The Bottom Line

Budgets are about choices. Senate Democrats have agreed to $3.5 trillion to fund a package of physical and social infrastructure, with funds raised by increasing the minimum income tax rates on corporations and very wealthy people (household incomes more than $400,000/year).

So the budget is set. The proposed $50 billion nuclear subsidies would come out of that budget–diverting funds from other programs, priorities, and investments. By our calculations, knowing that President Biden’s American Jobs Plan proposed $469 billion for renewable energy and other electricity infrastructure, the nuclear subsidy would take up more than 10% of that budget. This would be a massive amount of money to waste on a program that would not create a single job, would stall progress on climate action, and perpetuate environmental injustices in communities across the U.S.

Take Action!

Tell President Biden, Vice-President Harris, and your representatives in Congress: “No Nuclear Bailouts in the American Jobs and Families Plan – Invest in American Jobs and a Just Transition to 100% Renewable Energy by 2035!”